Lotr Bfme Free Download

| Platforms: | PC |

| Publisher: | Electronic Arts |

| Developer: | Electronic Arts |

| Genres: | Strategy / Real-Time Strategy |

| Release Date: | December 6, 2004 |

| Game Modes: | Singleplayer / Multiplayer |

The Lord of the Rings’ real-time strategy game falls short of its mark.

Gandalf has an impressive set of spells.

The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II (LOTR: BFME II) is a real-time strategy game developed by EA Los Angeles and published by EA Games.It is the sequel to Electronic Arts’ 2004 title The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth. And based on the fantasy novels The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit by J.

- Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II (BFMEII) is a real time strategy game developed and published by Electronic Arts.Lord of the Rings: BFME II is based on the fantasy novels The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit JRR Tolkien and a live-action film adaptation of the trilogy.

- Lotr bfme free download - War List for LOTR, Neverwinter Nights LOTR The Dunedain Campaign, Warcraft III - LOTR map, and many more programs.

Just as Peter Jackson’s spectacular Lord of the Rings movie trilogy evoked awe for its masterful visual presentation, the terrific-looking Battle for Middle-Earth likewise manages to impress through graphics rather than substance. But the films were exhilarating all the same, while the game falls short. It effortlessly trumps War of the Ring like a Nazgul but can’t hold a candle to meatier fare like Dawn of War. It “simplifies” the usual real-time strategy gameplay—removing or dressing down tactical options, unit types, depth, or any semblance of linear narrative— and becomes a repetitive grind.

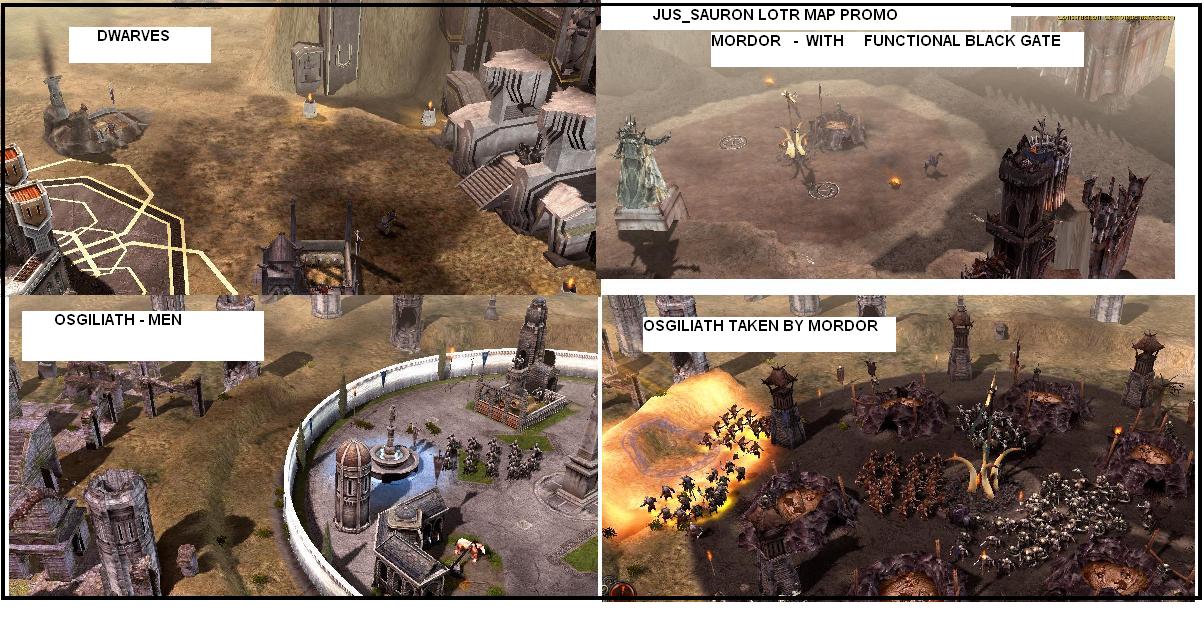

Four playable factions are available: Gondor and Rohan for the Good side, with Saruman’s Isengard and Sauron’s Mordor answering the cattle-call for Evil. As in the Kohan series, infantry and archers are created in squads of five or ten, although bigger fun-bets like heroes, mountain trolls, and Nazgul arrive in sets of one. The designers commendably do away with peon convoys by having a single lump resource type —called, aptly, “resources” — and by providing a limited number of real estate “lots” on which to place your structures. As your economy gets rolling by establishing expansion farms or slaughterhouses at the limited number of designated spots, you prune away the ones at home to make space for your now affordable Troll cages or Mumakil pens.

The rub is that buildings can only produce higher tier units once they’ve acquired sufficient veterancy, which accumulates only through making sufficient numbers of cheap units that count against your population cap. So you basically create them to die by the legion in order to gain access to their hardier successors. This mercenary tech model may be psychologically well suited to Mordor or Isengard, but deliberately sending Gondor infantry off to die leaves you feeling a bit like Denethor on a grumpy day.

Like Dawn of War, you expand by controlling certain points on the map that allow you to build outposts and settlements; eventually, when you take over an enemy, you can pay to construct a new citadel on the ashes of his old one. Only citadels, though, can make defensive towers, which, especially on larger maps with widely spaced choke points, leaves your lumber mill/farm outposts a little exposed. As a result, many games tend to degenerate into sluggish exchanges of ebb and flow as each side strives to capitalize on enough of an economic edge to secure victory. (Tolkien and economy just don’t mix.)

Although both infantry and hero units gain experience and increased abilities, strategic niceties such as flanking maneuvers and battle formations are absent, the variety of unit upgrades spartan and, Nazgul screeches notwithstanding, battle morale doesn’t seem to be a gameplay factor. Yet the game arbitrarily takes away control left and right: you can’t remove archers from a sentry tower once you’ve garrisoned them, nor separate archers and infantry once you’ve combined groups of each to create a more effective battalion.

Overcompensating handsomely for this comes a strikingly colorful palette of hero units and god powers that keep you playing. With each kill, your units gain not only experience but contribute points toward a set of powers granted by the One Ring or the Evenstar. These effects range from economic and armor bonuses to summoning a Balrog or the Army of the Dead. You can also use resources to purchase hero units like Gandalf, Saruman, Aragorn, or the hobbits, who become quite powerful if carefully shepherded and may be revived for a goodly sum when slain. Ian McKellen, Sean Astin, and the rest of the movie cast lend their voice talents to lines that sound more or less transcribed from the movies.

Single-player campaigns of above-average length are available for both factions, and rewriting the history of Middle-Earth from Mordor’s perspective proves strangely satisfying. As in Rise of Nations, you choose each battleground from a lush, colorful “living” map, with control of regions providing various bonuses such as extra resources or higher population caps in future battles should you prevail. Although the diverse missions predictably feature every encounter from the movie trilogy, in addition to a flurry of made-up ones like an orc assault on Lothlorien, they seem rather randomly linked. The Good campaign opens with the Fellowship battling its way through Moria, without any even cursory pre-game context, and leads to a bizarre anti-climax that has you as an uncharacteristically frantic Gandalf running around in circles avoiding the hooves and whipfire of a stomping Balrog.

Although your persistent armies are shrewdly retained from mission to mission, losing a hero such as Aragorn or Boromir is rendered meaningless by their inexplicable re-appearances at later junctures when the plot calls for it. It just rings false, and kind of dopey. There’s also an abundance of the tired missions where you excruciatingly micromanage a small squad of bad-ass heroes through a grueling, twisty labyrinth. These headachy maze forays are difficult to design, and a drag that teach little in the way of game mechanics.

Battle for Middle-Earth may not be the reinvention of the wheel but it’s certainly a good Lord of the Rings game. Real-time strategy’s a tougher racket to break, after all, and making one based on the Tolkien mythos must be a daunting prospect. How, indeed, does one balance, configure, and encode into robust gameplay for the ages a deliberately arcane literary conflict that was defined from first page to last as that of a weak few struggling desperately against a powerful many? Whatever the formula, this game valiantly tries and sometimes manages to get it right.

System Requirements: Pentium IV 2.5 GHz, 512 MB RAM, 64 MB Video, WinXP

- Buy Game

www.amazon.com - Manual

archive.org